Japan, an imperial power in history, has gone through various transformations in many areas such as economics, politics, consumerism, popular culture etc. And such transformations have surely changed Japan’s influence in the world after World War Two. Among the areas of vast transformations and novelties that Japan has gone through, I am particularly interested in Japan’s domination of the global popular culture, which has empowered both Japan’s economy and Japan’s soft power in marketing its culture to the youngsters all around the world. Therefore, in this paper, I will be focusing on what aspects of Japanese popular culture commodities, such as Pokemon products, have concurred, in a very genius way, with the type of life offered by modernity. I will be looking at three modern aspects which concur with the ideas that such products offer. I believe that Japan, a country which is considered a priority as a touristic destination for youngsters, and its relations with the rest of the world could be understood by digging into what makes the Japanese imagination and the marketing strategies an aspiration for the young people around the world, therefore, changing Japan’s relations with the rest of the world positively.

Firstly, the concept of a ‘child’, when dug deeper, could be perceived as a very modern concept. It is modern precisely because there are clear legal boundaries that define who is a child and who is not (an example is the notion of ‘age’ of consent). And as a child, you are deprived of many responsibilities because the state claims that a child is incapable of taking responsibilities, and therefore, it is the state that should take care of the child, be it in education or healthcare. And this binary division between a child and an adult makes childhood seem more intriguing, in a way that you are free of worries of responsibilities which you would face in the modern capitalist world, as an adult. Therefore, today, most adults and youngsters wish to go back to the care-free life of a child. And this is where Japanese genius of kawaii culture comes into play. According to Kinsella’s article, many respondents of her said that kawaii is linked with people being childlike (Kinsella, 238). Also, when Kinsella asked the question: “When you think of adulthood what comes to your mind? (Kinsella, 241)”, many replies stressed on the harshness of adult life and the responsibilities (Kinsella, 242). Therefore, the fear of ‘responsibilities of an adult’ imposed to youngsters and adults by modernity, makes Japanese cute culture a great option for temporarily making individuals feel like unaccountable children, or for making individuals walk across their memory lanes of their own childhood. Since the idea of relating negative emotions with ‘being an adult’ is not only apparent in Japan, but also in the rest of the world, “an association is made between Japan’s influence in global culture and the circulation of its (entertainment or recreational) goods to overseas. (Allison, 37)”.

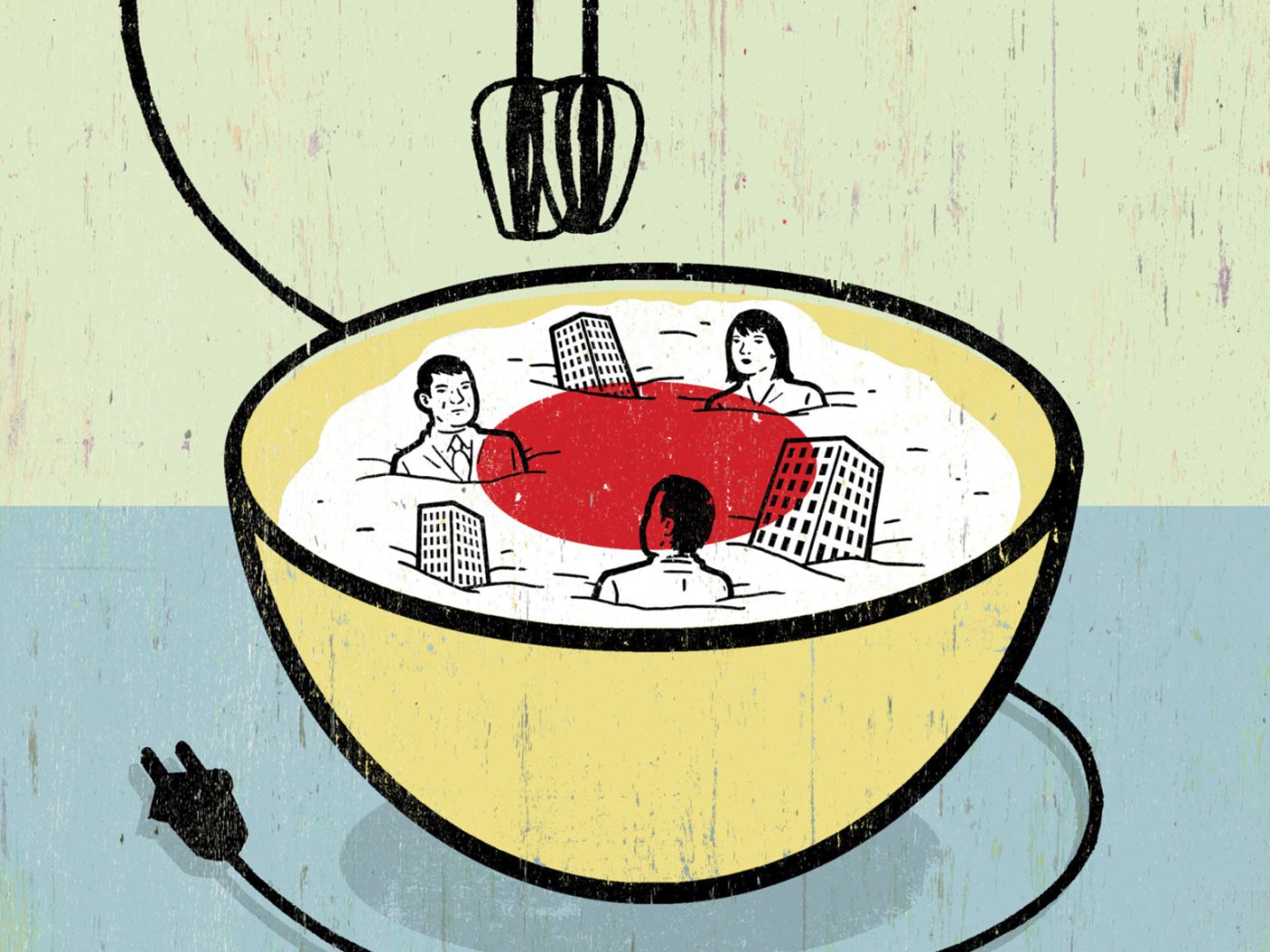

Secondly, when we talk about the modern world, especially with the emergence of neoliberalism, we can say that modernity has formed a binary understanding of the ‘public’ and the ‘private’ life of the individual. In public life, one is expected to behave rationally and put effort in maximizing the profit one makes from his/her available resources (also known as the idea of ‘rational maximizer’). On the other hand, private life is supposed to be where an individual is expected to be the emotional being and spend time with friends, family, and express one’s own ‘true self’, hidden from the public life. And this is where Japanese kawaii products play a role in helping one cultivate his/her ‘true feelings’ within the family with other family members, by using the idea of ‘cuteness’ offered by the kawaii products which can be adored by the whole household. Anne Allison gives examples how such products become a unifying means of cultivating emotions within the family: “young mothers who play Pokemon with their children after school; a housewife whose entire family likes Pokemon, with each member having his or her own favorite…” (Allison, 35). Hence, with the importance put to pursuing ‘true emotions’ in private spheres, such as the family, by modern life, Japanese commodities offer a mutual ground for individuals to fulfil such emotional needs within the household.

Lastly, another alluring trait of kawaii commodities such as Pokemon is, at times, the underlying logic embedded in the commodity. For instance, Allison argues that: “The fact of ‘getting’ is the very logic of the Pokemon game is a sign of the progression of the entwinement of play in commodity acquisitiveness. ‘Gotta chatch ‘em all’ is the slogan by which Pokemon is marketed … Metaphorically, however, catching stands for the player’s relationship to this entire play world, which is situated within the world of consumerism, which Pokemon itself mimics in play(ing) capitalism.” (Allison, 47). She further formalizes her theory in her article “Millennial Monsters”. So, in a way, Japanese games like Pokemon are not so different from reality yet take place in an imaginative world. It offers some sense of reality because, subconsciously, one can relate his/her way of living to a that of a cute world. Perhaps, it is precisely this reality/imagination duality of Pokemon games which make them the best choice when it comes to spending time in an imaginative yet not so different world. And that world, offered by Japanese games, is basically ‘today’s modern capitalist world without the stress and negativity’.

In conclusion, combining the three aspects of modernity which I have discussed, the concept of ‘child’, private-public life, commodity acquisitiveness, with what Japanese products, such as toys or games of Pokemon, offer to the consumer, we can see a harmonious concurrence between the two worlds. If the real world brings a problem, Japanese ideas solve it; and if the real world provides a new way of living, Japanese ideas presents that way of living with a mold of cuteness. And because of such novelties that speak to both youngsters and adults, the global perception regarding Japan has changed drastically after World War II. Hence, if one is to ask the question: “How have Japan’s relations with the rest of the world changed post-WWII period?” one answer would be that Japan’s relations with the rest of the world has changed more on the individual level than of larger waves. Because Japanese commodities have, overtime, provided many individuals a source of escape from the negativity in their modern lives, people have come to admire the Japanese as they have had huge impacts on people’s identities in their private spheres. And so, today, Japan is able to impose their soft power of popular culture through individuals and carry positive relations with the rest of the world in individual levels.

References

Sharon Kinsella, “Cuties in Japan,” in Lise Skov and Brian Moeran (eds.). Women, Media, and Consumption in Japan. University of Hawaii Press, 1995, p. 220-254.

Allison, Anne. “Cuteness as Japan’s millennial product.” Pikachu’s global adventure: The rise and fall of Pokémon (2004): 34-49.

Allison, Anne. Millennial Monsters. “Pokémon: Getting Monsters and Communicating Capitalism,” 192-233.

Leave a comment