Mattingly, Cheryl. 1998. Healing Dramas and Clinical Plots: The Narrative Structure of Experience. Cambridge University Press.

Carr, E. Summerson. 2010. Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety. Princeton University Press.

Given how all thought systems, aesthetic judgments, or moral frameworks are deeply embedded in the flow of the lived world, human experience becomes the ultimate source of value and meaning and a broker of what is perceived as reality. Such significance then calls into question the limits and dynamics of representing or expressing experience. Therefore, many scholars have eagerly probed into the relationship between narrative and experience, and some have problematized the extent to which our words represent our inner worlds. With its sensitive examination of experience, language, and interiority, care work in the context of therapy inevitably brings such discussions to the surface through practical ways of engagement. Two thought-provoking ethnographies, Healing Dramas and Clinical Plots: The Narrative Structure of Experience by Cheryl Mattingly and Scripting Addiction: The Politics of Therapeutic Talk and American Sobriety by E. Summerson Carr, tackle some of these questions and wonderfully present the therapeutic work of two groups of people respectively: occupational therapists and addiction therapists. While Mattingly looks into the ways occupational therapists utilize the power of narrative in the healing of severely injured or disabled people, Carr investigates the discourse on “healthy” and sober language during addiction therapy and the ways such ideologies of language are played out among the therapists and drug users. In this writing, I will attempt to analyze both works while hoping to bring intriguing insights concerning the ways the two ethnographies may speak to one another concerning issues in the representation of experience, independence models of healing, and broader issues and tensions within the nature of care work of the therapists in question.

Narratives: Given or Made

Carr’s ethnography is based on more than three years of fieldwork following professional practitioners and drug-using clients through a network of social service agencies in a Midwestern city in the US in a context of economic downturn and welfare state retrenchment. She specifically focuses on the negotiations and verbal transactions between therapists and clients at “Fresh Beginnings”, “an outpatient drug treatment program in the center of this social service network” (p.2) which targets female addicts (mostly African-Americans). In this treatment program, like many others in the contemporary American context, we are presented with an ideology of inner reference. In other words, therapists in Fresh Beginnings saw addicts suffering from “the inability to read their inner states and render them in words” (p.4). This was especially apparent in how every client was met by “an epistemology which posited that the only sign of addiction could very well be the absence of symptoms” (p.82-83)—that is, denial. In other words, addiction was seen as a disease of denial and a disease of insight (p.90). In the therapists’ understanding, then, one’s state of ‘denial’ was not only constituted of denying one’s substance abuse but also an inability to see clearly who one was and what needed to change. Therapists also assembled a model of addicted subjectivity “in which layers of denial were topped by a thin if formidable layer of anger, which itself covered over a dense stratum of shame” (p.93). These therapists saw treatment as a matter of “detecting, penetrating, and disintegrating” (p.94) such layers that comprised the addicted subject whose psychic structure was “molded by a pre-institutional set of drug and drug-related experiences” (p.94). Therefore, recovery was all about coming to terms with “one’s true inner self that is purportedly denied in active addiction” (p.92). Consequently, therapists promoted a recipe for inner reference that took the acronym ‘HOW’ which linked therapeutic ideals of honesty, openness, and willingness along with the idea that “secrets keep us sick” (p.138).

On the other hand, Mattingly’s work consists of a two-year ethnographic study, beginning in 1996, concerning the work of occupational therapists in a teaching hospital in Boston. Her observations have led her to reconsider the relationship between narrative and experience as she realized how therapists and patients not only told stories but created “story-like structures in their interactions” (p.2)—which she refers to as therapeutic emplotment. More importantly, she saw these efforts in story-making as integral to the healing power of the practice of occupational therapists, which led her to this book that concerns the narrative structure of action and experience. To Mattingly, stories were not just told after experience but “were constructed while people were still very much in the midst of action” (p.5). Just like the work of her interlocutor occupational therapists, social actions, she argues, “are organized and shaped by actors so that they take on a narrative form” (p.19)—suggesting a homologous relationship between narrative and experience. In other words, narrative imitates experience “because experience already has in it the seeds of narrative” (p.45). This arises due to how, according to the author, actors have a need for narrative and therapists require their actions to get the therapy to somewhere along a desirable route—suggesting that action is yet an untold story and in quest for narrative. In this sense, the very ordinary acts of therapists, such as making patients play checkers, become imbued with meaning in a broader narrative. Given the ordinariness of the acts that patients are asked to do while therapists aim for a positive change, one could better see the significance of such intertwined action-narrative dynamics as “the essence of meaninglessness is when lived experience seems to be driven by no form than brute sequence” (p.47). To further elaborate by unjustly giving a very brief version of an ethnographic example, the interactions between Steven, a severely injured patient from a car accident who can only communicate with writing, and Donna, an occupational therapist, make Mattingly’s arguments more comprehendible. Steven has been out of bed first time since his traumatic accident and is reluctant to move or get up. Initially, Donna goes through a regular checkup of his breathing and other physical activities and says that he is doing better than the day before. Then, she hands Steven a comb and asks him to comb his hair—which she says is a good balancing practice—and compliments him throughout his efforts. And then Steven requests for a mirror and Donna jokes by asking whether he wants to make himself look good for his girlfriend. Then she takes him for a ride in a wheelchair to show him his new place. While showing him around, she mentions how he will be spending a lot of time in the facilities and working together and strengthen his body. At some point, Steven complains about a pain in the shoulder and the therapist responds that moving it is good and will make it stronger. Later, as they wheel to a large window looking over to the city, Donna says that she will not be there every day but that his family will take him out as he gets stronger. After asking whether he recognizes some of the monuments that can be seen through the window, they return to his room. Throughout the session, Donna emplots her actions by crafting them as part of a therapeutic story. The meaning of combing can be seen as a preparation to be seen by others he cares about, and this meaning is acknowledged by Steven by asking for a mirror. And the up-and-down ride they take through the hospital halls is turned into “a chance to see his new surroundings, a chance to see and be seen” (p.90). Such discrete acts suggest a theme of reentry into the public world. Steven agreeing to go for a ride, or comb his hair, also signals to Donna a motive to “move out into the world” (p.90). In other words, before Steven enters a world of others consisting of, say, his girlfriend, he will first begin his journey in a social world consisting of clinicians. And as they move through the facilities, Donna helps Steven personalize the hospital and see it through his version of it. And in this prospective story, “they work together and he becomes stronger” (p.90). Thus, we see the emergence of a story of reentry, freedom from an immobile body, institutionalized existence, and work and pain (p.91)—a story with a hopeful ending that emphasizes a difficult path that Steven has to work through.

Although Carr, in her work, focuses more on language than action, one could see how therapists in Fresh Beginnings too bring about certain ideologies of narrative that come to the surface in their practices and which, in some aspects, contrast Mattingly’s depictions. In the case of occupational therapists, we see a very interesting relationship between their therapeutic emplotments and time. The discrete therapeutic acts that make up a story in the healing of patients speak to a much larger time horizon and present a time order that is more “additive” than linear (p.64). The narratives that are co-authored by the therapists and patients may speak to different time periods and visions both in the past, present, and future—which Mattingly calls “time as a three-fold present” (p.64). Meanwhile, in the case of Fresh Beginnings, narratives are neither co-authored nor represent time as a three-fold present. Instead, the discourse on denial, anger, and shame constructs addiction as a story that belongs to the client’s life prior to therapy. Before the patient steps into the program, therapists are already very much equipped with social work theories concerning addicts and their subjectivity. Often, one’s addiction is traced to one’s experiences and feelings of anger and shame in one’s life experiences that, in theory, lead to addiction which gets perpetuated with denial—making up an institutional profile for the client. The aforementioned model of addicted subjectivity that centered on denial also suggested one’s self as a given inner truth to be explored or excavated by digging through the horizontal layers that obstructed the interiority. Thus, clients’ words were taken to not represent the reality that was obscured to them through their disease of denial—which precisely was what gave therapists their authority, that is identifying and articulating the truth on behalf of their clients (p.101). This approach to representation and truth then presents an anti-mimetic stance towards narrative which, as also touched upon by Mattingly in some parts of her book, contends that narrative, instead of having a natural correspondence between life as lived and expressed, transforms and distorts reality and experience. Paradoxically, in this framework, it is only the acceptance of denial that presents a correspondence between one’s words and interiority—turning the initial anti-mimetic stance into a mimetic/realist one. Hence, in Fresh Beginnings, one’s representation of one’s self could be evaluated through either of these contrasting stances towards narrative. Which domain one’s words fell into was ultimately decided by the extent to which a client conformed to the script of addiction provided and expected by the network of institutions she found herself in. To achieve a mimetic use of language that represented one’s inner self, an ideology celebrated both by the clinical discourse and broader American society, the client had to ironically perform and correspond to a given script of an ‘addict subjectivity and language’.

Depending on Independence

The semiotic ideology that was often stressed at Fresh Beginnings did not always play out as wished and, at times, was overturned by clients through their practical wishes. As was mentioned, Carr’s ethnography takes place at times of economic downturn and welfare state retrenchment in the US. In such context, one sees American debates on poverty being framed in terms of “dependency” (p.24) and policies that are aimed at producing ‘good’ independent and working American citizens. At the Fresh Beginnings program, the client is offered various services such as shelter and transportation through the network of affiliated institutions. Yet, these services are hinged on the individualized case file and progress of the client in a program that ultimately wanted to transform addicts into healthy individuals who were both psychologically and economically independent. Services like food, shelter, and even the custody of clients’ children teetered on the outcome of routine therapeutic interactions such as clinical assessments, individual therapy sessions, or self-help meetings. Therefore, clients anticipated and controlled how their words would be taken up by counselors, case managers, and therapists (p.3) by ‘flipping the script’. In short, flipping the script was “the performance of inner reference” (p.191). Script flipping aimed at reproducing therapeutic scripts with the exception that one did not actually match her “spoken words to their inner signifieds [thoughts, feelings, and intentions]” (p.191). A client flipping the script attempted to control and evaluate the dimensions of their therapists’ work “so as to control the distribute ones [referring to social services]” (p.196). The practice thus “both theoretically challenged and practically reproduced the semiotic ideology” (p.191) that was present at Fresh Beginnings. Although it was never entirely clear to the therapists or the ethnographer when one flipped the script, the practice pervaded throughout clients’ experiences and suggested the setting at Fresh Beginnings—intentional or not—one of a constant performance despite the efforts of therapists in eliciting authenticity.

When it comes to the therapeutic emplotments by occupational therapists, Mattingly challenges and complicates the assumption that “what narrative offers to the structure of experience of the self is coherence” (p.107). Continuity was not a primary motive for occupational therapists. Rather, the drive to create compelling therapeutic plots was more about locating desire—bringing back one’s interest in his/her life. Given how becoming disabled was to become disembodied and alienated from one’s body, locating desire through therapeutic emplotments entailed, at first, helping the patient articulate a new sense of self. In other words, “therapists’ efforts are directed, in part, toward a patient’s ‘re-embodiment’” (p.78). This further entailed and required patients to take responsibility for their condition and come to know their bodies (p.77). The idea is reflected in the words of an occupational therapist who describes her work: “Nurses do for patients, we help patients do for themselves” (p.74). The same idea is also present in a therapeutic session in which the therapist explains to the patient how he should know the side effects of his medicines, observe his body’s reactions, and know what to do in such scenarios. Her remarks not only suggest the patient to become his own pharmacist but also better know his ‘new’ disabled body and how to best treat it.

In the latter case, that of occupational therapists, we see how treatment is about instilling hope and a desire in the patient and constructing a journey of transformation that, from an ableist vision, supposedly leads to independence. The focus on getting rid of dependency echoes the motives of the institutional approaches mentioned in the former case in Fresh Beginnings. Mattingly emphasizes the co-authoring aspect of these therapeutic emplotments and how the patient has to actively take part in the story-making process. Yet, at times, “mismatches” occur between the therapist and the patient when the patient “cannot identify with the therapist’s hoped-for story” (p.149). Such struggles may result in a stalemate in which therapeutic time stagnates into repetitions with not much progress in the therapists’ eyes, leading to an exit in therapy. Furthermore, some therapists would feel anger towards such patients as a result of patients’ resistance to or lack of participation in the desired plot. If script flipping can also be perceived as a form of resistance to discourses on independence, then a common reaction among the two distinct contexts becomes apparent. Ironically, the institutional contexts in both cases depend on the discourses and language on independence to exist. Perhaps, one can arguably say that both Fresh Beginnings and the work of occupational therapists are built on such ideologies of independence. Yet, the power that is imbued within the discourse, practice, and institutional authority in both contexts is resisted in unique ways: either flipping the script or refusing to take part in a therapeutic emplotment that is ultimately dictated by the therapists’ hopeful-yet-ableist wishes.

Care and Hope?

I wish to end this combined book review by further contextualizing the nature of the work of these therapists in the two contexts—rather than the very individuals who dress themselves in these figures. Another important argument in Carr’s work is how, as long as therapists produced the ideological premises of inner reference, “the program and its practices were effectively insulated from clients’ critical commentary” (p.126). This was mostly due to how the clients were expected to only reference their inner states instead of bringing an instructional critique. As was previously discussed, the lack of inner reference was a signal of no progress/recovery. Thus, any institutional criticism brought by clients was dismissed as part of their addict talk which failed to find the blame in one’s self that is supposedly filled with anger and shame. As Carr’s ethnography presents, this issue would then lead to many problems in terms of representation of clients and plays a role in the inherent crisis in the institution that Carr describes. Although it was therapists’ care for their clients and hope for a rescue “that fueled what can otherwise be read as cold and simple dogmatism” (p.149), the ethnography presents the ways therapists are signed on to serve an institutional mission that was “committed to achieving lasting sobriety and self-sufficiency” (p.149) and practiced in accord with decades of clinical literature that prescribed ‘eliciting sober speech’ for achieving lasting sobriety. Therefore, the script of addiction and the practices that followed were more of a product of clinical literature, institutionalized representational economies, and broader ideologies on language and personhood in the contemporary United States than the initiatives of therapists and other figures at Fresh Beginnings.

Unlike, the more rigid and ‘scripted’ nature of the work of addiction therapists, occupational therapists’ work was located in a domain of ambiguity, in-betweenness, and creative improvisation. An efficacious therapeutic plot “depends on abandoning any formulaic structure” (p.166) and requires a close reading of the patient’s attitudes, inner states, lives beyond the hospital walls, etc., and flexibility in creatively maneuvering through a story whenever the patient seemed disconnected. Hence, combining all aspects of therapeutic emplotment, Mattingly argues how the work of occupational therapists is more like a secular healing ritual than practices of applied science (p.161). Yet, it was this nature of their work that put these therapists in a highly conflicted position in a biomedical institution that ultimately looked for measurable outcomes. As the author describes, occupational therapy bears with it a double vision of the body: “a biomedical conception which belongs to a mainstream medical culture, and a phenomenological conception” (p.143) which is in the nature of their therapeutic work. The phenomenological aspect of their work is neither documented nor formally recorded. Despite how the therapists also see the value and ‘magic’ of the creative parts of their work, they can’t avoid concerns over whether they look sufficiently technical and specialized and are “mistaken for lower caste professionals such as nurses aides or recreational therapists” (p.148). Such concerns not only lead therapists into sometimes shutting down what may seem like successful stories/plots (p.130) but also trying to “stay very near the surface of the patient’s life” (p.147)—meaning to stick to a “superficial and broad noting of facts about patients’ life rather than exploring patients’ concerns and meanings” (p.146). Nevertheless, as in the previous case, it was therapists’ care and hope that had to be served in the cold and disfigured plates shaped by institutional demands and dynamics which—if successful—brought some form of change and transformation in the fragile lives of their interlocutors.

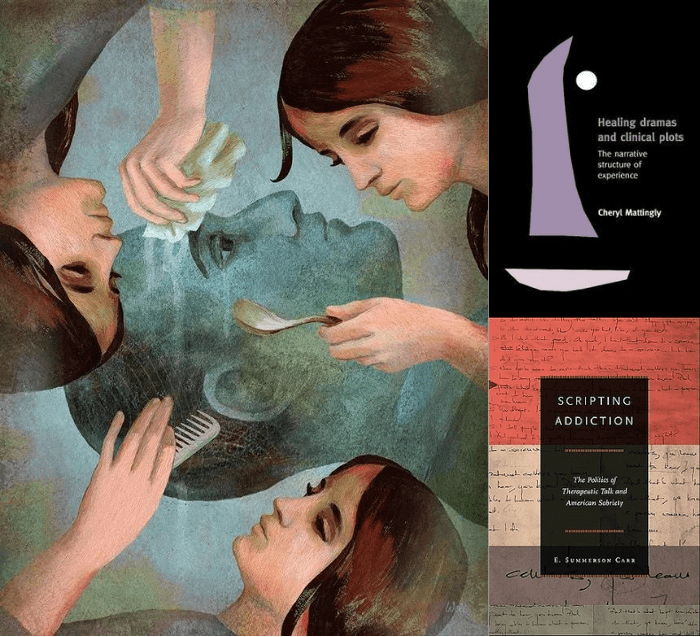

Image: Nursing Care at Home by Allice Wellenger

Leave a comment